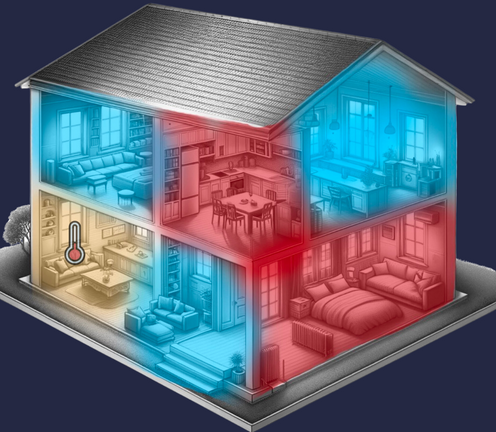

Did you ever think your room was the coldest in the house and wonder why the thermostat wasn’t maintaining the temperature you set? This often happens because most thermostats are “blind” against the temperatures of other rooms; they regulate the entire house based on the temperature detected by the sensor in the thermostat itself. This approach has been accepted based on the assumption that there isn’t much temperature discrepancy between rooms in a house. While this assumption might hold for a one-bedroom home, I have significant doubts about its validity in houses with multiple rooms, like townhouses in the US.

Therefore, I decided to conduct a study to understand the severity of this issue. For this purpose, I analyzed data from a smart thermostat company, Ecobee. Fortunately, Ecobee recognized this problem and began offering remote sensors that can be placed in different rooms. The Ecobee thermostat then controls the house’s temperature based on the average temperature of the occupied rooms. How succesful this approach was is a part of the discussion below.

My initial analysis revealed that with traditional thermostats, there could be a discrepancy of 3°F from the set point. Switching to Ecobee showed a 45% increase in thermal comfort, although it still had limitations, overcooling by up to 6°F from the set point to balance the temperatures in other rooms. On a larger scale, individual rooms showed expected deviations ranging from -3.5°F to +2.2°F from the set point. Thus, averaging alone is not a sufficient solution since you are just averaging the problem and not actually solving it. In the third part of my study, I explored the reasons behind these deviations, such as poorly insulated rooms, HVAC systems not adequately serving upstairs rooms, and high solar gain. In 95% of the houses studied, high solar gain was found, 85% had low heating coming input, and 70% suffered from poor insulation. Lastly, I investigated whether thermostats are typically placed in a position that accurately represents the thermodynamics of a house. The answer is no for most houses. This is just the tip of the iceberg and I’d really recommend you to read the paper. You can check my work from the citation below (or from the tattoo of the DOI number I got).

Overall, we see that this is a design limitation of existing houses. Potential solutions could include retrofitting based on room-level data or advanced control strategies that account for these deficiencies. That being said, if you live in a house with multiple people (especially in an undergrad apartment), now you can show this blog post to your roommates and say, “See, I told you guys my room wasn’t getting enough heat” (been there, done that)!

Mulayim, O. B., & Bergés, M. (2023, November). Unmasking the Thermal Behavior of Single-Zone Multi-Room Houses: An Empirical Study. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings, Cities, and Transportation (pp. 21-30).